Design thinking is an approach to problem solving and the development of new ideas by fostering collaborative creativity. It originated in design research, which explored the work processes of professional designers and tried to find out “how designers think”. Design thinking was developed in the mid-1980s by the innovation agency IDEO and became very well known through the founding of the Institute of Design at Stanford University.

How does Design Thinking work in projects?

It is not a specifically defined method, but rather the use of a combination of methods that focus on process tasks such as observing, generating ideas and creating prototypes. The following principles guide its use (cf. Lewrick/Link/Leifer 2020):

- We strengthen our curiosity to understand issues and problems in depth.

- We open ourselves to new possibilities.

- We say goodbye to preconceptions of “how things work”.

- We put aside expectations about what will happen.

- We ask simple questions.

- We try things out and learn from them.

Essentially, there are seven steps in the process:

- Understanding

- Observe

- Define point of view

- Develop ideas (collect, evaluate, prioritise)

- Develop prototypes/models of the best ideas

- Test

- Reflect

Why is Design Thinking suitable for innovation processes in the social and health care sector?

Six facts speak in favour of applying Design Thinking to projects in this environment:

- Humans are the starting point.

- Problem awareness is created.

- Work is done in heterogeneous and interdisciplinary teams.

- Prototypes are tested and feedback is important.

- Complexity is accepted as part of the problem.

- Because work is done in shorter and longer cycles.

Innosuisse uses design thinking as a methodological orientation framework for the Innovation Boosters it funds, see mission statement and guiding principles.

In order to understand social innovation, it is important to first take a look at what innovation can all be.

Forms of innovation

In general, innovation refers to something new, something that deviates strongly from previous expectations and thus it often surprises. In connection with novel ideas and their implementation in practice, innovation therefore refers to both (development) processes and results. Recognition of whether something qualifies as an innovation can only occur through comparison within a specific temporal, geographical, or even professional context. What is considered innovative today may no longer be so in just a few years. What is innovative in one place may already be commonplace elsewhere. Innovations within the context of social and healthcare may have already been implemented in other fields. Innovation can thrive in all domains of science and society, including technology, art, tourism, urban planning, and medicine, among others. Innovation processes are marked by uncertainties and risks. When approaching a problem in a novel manner, setbacks, project failures, or unforeseen side effects may occur. This is precisely why innovations need “risk capital”. The Innovation Booster “Co-Designing Human Services” provides precisely the kind of support that potentially innovative development ideas within the social and health sector need.

The added value of social innovations

Social innovations do not refer to a product in the traditional sense, such as commodities or means of production, but rather to social contexts. It is about changing social practices and relationships and contributing to the empowerment of certain (vulnerable) population groups. Social innovations, therefore, empower individuals whose health, well-being, and social participation are impaired or at risk for various reasons. Social innovations offer a novel approach and solution to a social problem, providing added value that, in turn, significantly benefits society as a whole. They have the potential to fundamentally, comprehensively, and permanently change practices. They prevail over what has gone before because they are perceived as a more effective, sustainable, equitable or even fit approach to a social need or problem. The impact is transformative if the changes also affect the causal contexts that have led to a social problem. A good example of this is the principle of harm reduction, which has become established in addiction aid and aims to reduce the negative consequences of drug use by prioritising care and prevention strategies,

Social innovations can be differentiated according to the social level they target. One speaks of micro-, meso- and macrosocial innovations (see Parpan-Blaser/Hüttemann 12019:81). Another possibility is to differentiate according to the degree of innovation; one speaks of incremental, evolutionary, expansive and radical changes (see Osborne 1998). The third variant is the social field to which they refer, i.e. housing, health, work, coexistence, etc.

Source:Burkett

Co-design is a method for actively involving a wide range of people in design and implementation processes. It involves incorporating collective experiences and needs into improvements and innovations so that services and outcomes are created or optimized to the best of their potential.

How does co-design work?

It means that, instead of an expert-driven process, you engage in a participatory process that is user-driven throughout all phases. It is not about consulting people only at the initial stage, but involving them in a learning process about what works and how we can innovate. This is to ensure that services to support people are able to reach everyone. Therefore, co-designing aims not only to include the voices of end-users, but also to build mutual understanding across the service system (see Burkett).

Basic ideas and advantages of co-design

Co-design is guided by the following principles, among others:

- The group starts with questions, not solutions, and with curiosity, not certainty.

- It involves learning with and from people who have “lived experience” of a topic, which for professionals often means leaving the office and comfort zones.

- Co-design is an on-going process, not an event: certain structures are needed to build relationships that foster trust, open communication and mutual learning.

- Co-design is likely to involve conflict, difficult decisions, risks and failures. Therefore, it should be approached with a clear understanding of these potential challenges.

This approach to work offers several advantages:

- It encourages viewing challenges or problems from various perspectives.

- Different backgrounds and experiences as well as diverse knowledge lead to a deeper and complex understanding of issues.

- Multiperspectivity helps to leave the beaten track when it comes to developing ideas.

What is important to bear in mind when co-designing?

Anyone working with co-design needs to pay attention to the following points:

- Participants should be open to different viewpoints.

- Differences should be valued, unequal emotional involvement should be acknowledged.

- Individual expectations of benefits should be transparently communicated.

- Forms of collaboration should be chosen to allow everyone to contribute their strengths effectively.

- Goals, steps, roles and tasks must be made transparent and negotiated.

- Regular moderation of discussions and processes is essential.

- Periodic reflection on cooperation is important.

Measures should be taken to address unequal resource availability, such as considering whether participants are involved during working hours or in their free time.

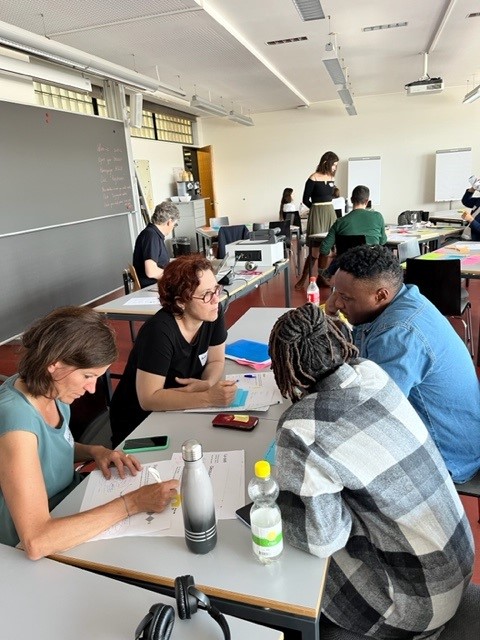

Co-designing at the Social Innovation Forum 2022

Co-designing at the Meeting the innovation teams 2023

The level of innovation for the ideas we support aims to be as high as possible. However, in highly regulated areas like social and healthcare services, fundamental changes in the form of radical innovations require significant time. The Innovation Booster "Co-Designing Human Services" fosters initiatives with the potential to achieve this.

By radical innovations, we mean the introduction of fundamentally new approaches that profoundly change how services in the social and healthcare sectors are delivered, organized, and/or financed. Unlike (so-called incremental) improvements, radical innovations involve a departure from existing systems and typically require new skills, processes, and infrastructures.

Radical social innovations can also be seen in the tradition of movements (e.g., radical social work) advocating for social and healthcare services not to be overly focused on the individual. Instead, they emphasize addressing and transforming the societal factors that cause social and health issues. Calls for systemic change on this scale are often supported or initiated by social movements.

Argumentation (in German only)

Design of innovation processes

Eurich/Glatz-Schmallegger/Parpan-Blaser (2018). Gestaltung von Innovationen in Organisationen des Sozialwesens.

Klein/Laville,/Moulaert (2014). L’innovation sociale.

Cassani (2017). Design Thinking per le imprese sociali.

Project management

Gächter (2019). Projektmanagement konkret

Bouchaouir/ Dentinger/Englender (2017). Gestion de projet.

Romano V. (2022) Project Manager oggi. Come realizzare progetti in tempi ridotti, in un mondo veloce e complesso.

Problem solving

Alberti/Gandolfi/Larghi (2016) La pratica del problem solving. Come analizzare e risolvere i problemi di management.

Design thinking methods

Lewrick/Link/Leifer (2020). The design thinking toolbox (available also in German and Italian)

Biso (2020). Design Thinking. Accélérez vos projets par l’innovation collaborative.

Co-operation in heterogeneous teams

Driessens/Lyssens-Danneboom (2021) Involving service-users in social work education, research and policy.

Müller de Menezes/Chiapparini: «Wenn ihr mich fragt…» Das Wissen und die Erfahrung von Betroffenen einbeziehen Grundlagen und Schritte für die Beteiligung von betroffenen Personen in der Armutsprävention und -bekämpfung (also in F/I) www.gegenarmut.ch/beteiligung

Les Chercheurs Ignorants (2015). Les recherches-actions collaboratives. Une révolution de la connaissance.

Caporarello/Magni (2015) Team management. Come gestire e migliorare il lavoro di squadra.

Innovation process design

Eurich/Glatz-Schmallegger/Parpan-Blaser (2018) Gestaltung von Innovationen in Organisationen des Sozialwesens.

Klein/Laville/Moulaert (2014) L’innovation sociale.

Cassani (2017) Design Thinking per le imprese sociali.

Project management

Gächter (2019) Projektmanagement konkret

Bouchaouir/ Dentinger/Englender (2017) Gestion de projet. Vuibert.

Romano V. (2022) Project Manager oggi. Come realizzare progetti in tempi ridotti, in un mondo veloce e complesso. Milano: Franco Angeli

Design Thinking methods

Lewrick/Link/Leifer (2020) The design thinking toolbox [available also in German and Italian]

Biso (2020) Design Thinking. Accélérez vos projets par l’innovation collaborative. Dunod.

Cooperation within heterogeneous teams

Driessens/Lyssens-Danneboom (2021) Involving service-users in social work education, research and policy [expectionations, roles, team buidling, etc.]

Müller de Menezes/Chiapparini: Guide pratique : « Et si vous nous donniez la parole » – Tenir compte des savoirs d’expérience des personnes concernées [participative user involvement]

Les Chercheurs Ignorants (2015) Les recherches-actions collaboratives. Une révolution de la connaissance. Presses de l’EHESP.

Caporarello/Magni (2015) Team management. Come gestire e migliorare il lavoro di squadra. Milano: EGEA.